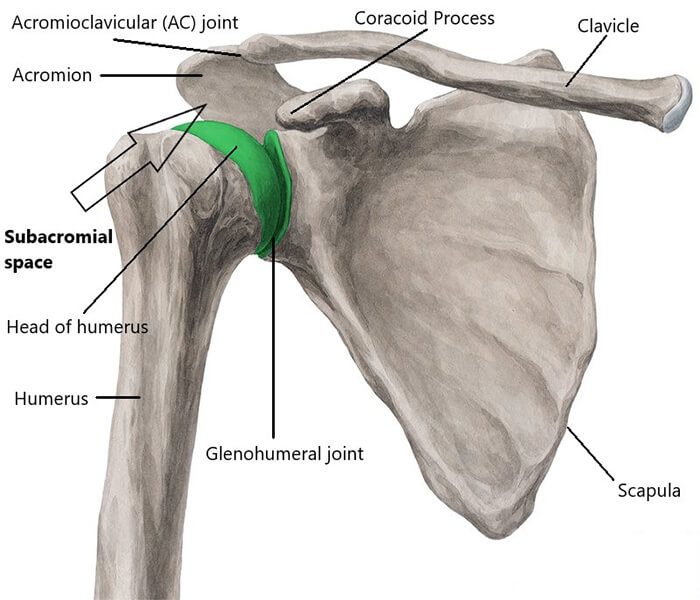

Firstly, it is important to understand that shoulder impingement is not a diagnosis, it is a clinical sign which is used to establish a diagnosis. Shoulder impingement occurs when the rotator cuff tendons are impinged as they pass through the subacromial space formed between the acromion, coracoid process and acromioclavicular (AC) joint above and the glenohumeral (shoulder) joint below (see diagram for details).

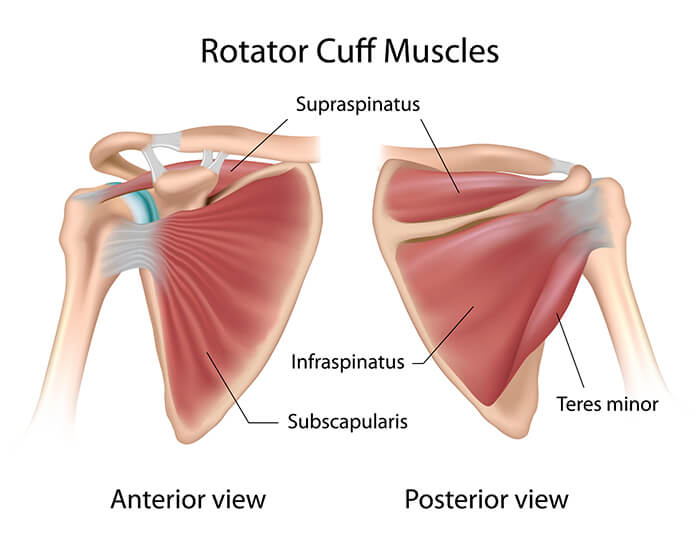

The scapula and humerus normally work together and move in a coordinated rhythm. We call this “scapulohumeral rhythm”, and when operating correctly, the subacromial space is maintained. The ratio of movement between the humerus and scapula is approximately 2:1, i.e. if the humerus is flexed/abducted 120°, the scapula is upwardly rotated 60°. If the scapula is poorly positioned (i.e. excessively protracted, elevated or downwardly rotated, or a combination of these positions) during shoulder movement, the head of the humerus jams into the acromion and impinges the subacromial structures – rotator cuff tendons and subacromial bursa.

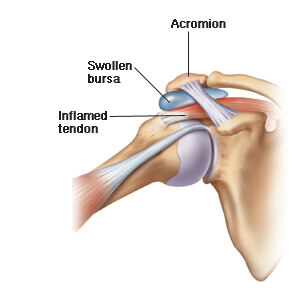

Impingement causes mechanical irritation of the rotator cuff tendons, leading to swelling and pain, most commonly experienced in the lateral shoulder. The bursa can also become irritated, swollen and painful, leading to reduced shoulder range of motion, muscle weakness and further changes in shoulder dysfunction.

Diagnosis associated with shoulder impingement:

- Scapula dyskinesis – in layman’s terms, poorly positioned shoulder blades that don’t move very well – very common!

- Rotator cuff muscle strain or tendinopathy

- Sub-acromial bone spurs and/or bursitis

- AC joint arthritis and/or bone spurs

- Glenohumeral joint instability

- Biceps tendinopathy

- Cervical radiculopathy

Treatment for shoulder impingement largely depends on a thorough and accurate assessment. The priority is to determine which muscles are weak and need to be strengthened; which muscles are overactive and need to be released (through massage or dry needling); which movement patterns need to be corrected; are further investigations (e.g. Xray or US) required; and does an Orthopaedic Specialist need to be consulted??

In most cases, some passive treatment coupled with a heavy emphasis on specific exercises usually does the trick. Progress can be up and down for the first few weeks as patients balance the right amount of load with technique. NSAIDs are occasionally needed and in severe cases a corticosteroid injection may be administered. Usual time to heal can take anywhere from 4 weeks to 3 months, depending on the severity.